A hand-pumped well in the shadow of a cell tower.

Although Burkina Faso is an underdeveloped country, the people are striving to advance in many areas. It is full of contrasts: patches of modernization right next to rural traditions. It’s a place where one can find cell phones out in the farthest villages which have no electricity. People charge them on car batteries and stand on the one hill or next to the one tree where there is a signal. It’s a place where a satellite dish can be found in a yard enclosed by a grass mat wall. It’s also a place where the medical system is struggling to provide, where one can get laparoscopic surgery in the capital for $1400, and yet people are dying in the villages for lack of $2.

A satellite dish peeking out from a temporary grass mat fence.

Many people are trying to change things, but it’s a huge task. As is true everywhere, some people are doing their best, working hard, while others just coast. However, even the people working hard are up against so many obstacles. There is a physical side to the difficulties in that there just aren’t enough resources for better facilities, equipment, or materials. There are also obstacles to overcome in the attitudes of the people, both the doctors and the patients.

Materially, it is plain to see that Burkina just doesn’t have the resources necessary to keep equipment and facilities up to date. In the capital city of Ouagadougou (Wagadoogoo), one can find almost all the usual equipment. There is a machine for MRIs and one for CAT scans, but if one of them breaks down, the patient just has to wait until it’s repaired. There is a place that specializes in heart problems as well as several sonogram machines in the city. Facilities vary in age and cleanliness. The most knowledgeable doctors are there; however, there are just some things they can’t do or have to send away to get tested. They are limited by the equipment and supplies.

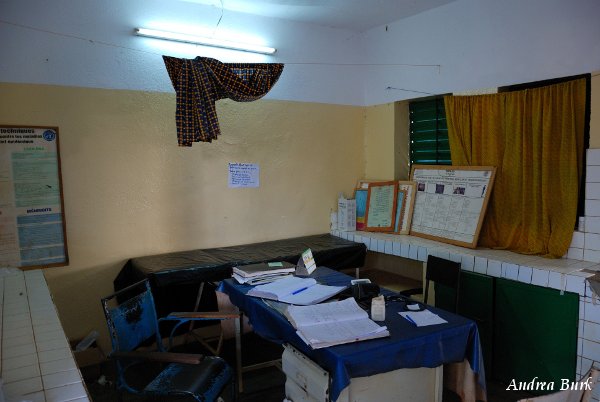

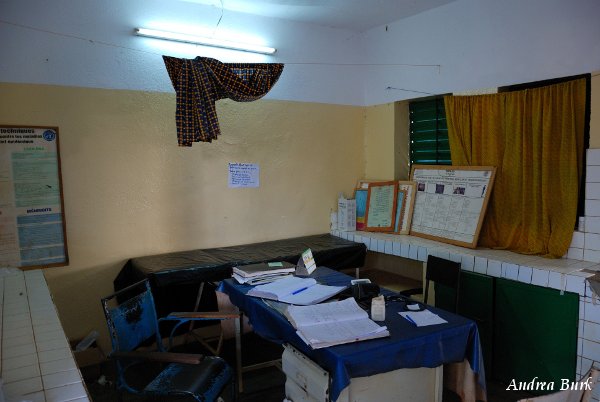

The nurses' station in Dano. It used to be the only hospital in town.

As one travels out further to smaller towns, standards are lower because resources are fewer. Most of the pictures here are from the older hospital in Dano, which is really more of a nurses’ station. The new hospital has more capabilities, but still can’t do everything they can do in Ouaga.

The doctor's office where patients go when they first come in.

One of the rooms in the small surgery operating room.

Small operations are performed here.

Doctors have worked extremely hard to achieve their knowledgeable position and should be applauded for that; however, many times pride has taken over and there seems to be a superior attitude. This is definitely changing, but is still rooted in a hierarchical, respect-based society. Their pride as well as their being assigned to a region where they don’t speak the language can keep them from taking the time to explain an illness to a patient. In the U.S., there are magazine articles and television shows everywhere teaching about medical issues and illnesses: how to prevent them, the signs and symptoms, and even how to treat some things. In Burkina, most people from the villages can’t even read, and often return from the doctor without a firm idea about what is wrong with them, much less a good understanding of how to live with the illness or prevent it. Many times they are too intimidated to ask questions about their own health.

The tiled, run-down operating table.

In more developed countries, if we get sick, we tend to go see a doctor right away. We see it as a right and the natural course of things that we get medical advice and the needed medicines. When someone dies, it’s extremely rare that we don’t know the reason. In the villages of Burkina, people are much more accepting of illness and death as the norm. Some of this is due to lack of money for medicines and transportation to the doctor, but some is due to lack of knowledge, an attitude of fatalism, or an inferiority complex coming from the generational poverty. In their view, important people and those with money can go to the hospital and buy medicines, but it seems almost impossible for them to have that same privilege. They just don’t see coming into town to see the doctor as an option sometimes; therefore, they wait so long to seek help that it is often too late. The person ends up dying in the hospital, fostering the idea that one goes to the hospital to die, and therefore discouraging people from wanting to seek out the hospital. It’s a cycle that needs to be broken.

We recently had two cases of this. One woman had been sick for several days, having already been told by her local nurses’ station that she needed to go have her appendix taken out. She put it off until it had burst, but fortunately she got to the hospital in Dano in time and lived. However, another woman had been sick off and on and this time they waited too long to bring her in. The hospital didn’t even want to admit her at first, perhaps to save the family’s meager money or maybe trying to stop the misconception that the hospital is only a place to come to die. In the end, she was at least able to die comfortably and with dignity in a hospital bed.

The maternity ward at the hospital.

It is very easy to get frustrated and to question why they don’t seem to care or want to change their situation, but we have to understand that many of these attitudes are deep-seated, prevalent in many cultures across Africa, and have far-reaching implications in society as a whole. It’s also important to remember that we should not stereotype and assume everyone is the same in another culture. Despite patterns, each person and situation is unique.

There is a good article that succinctly explains the general mindset of traditional African culture, written by an atheist who believes that Africa needs God, not just aid work. He states, “Every man has his place and, call it fear or respect, a great weight grinds down the individual spirit, stunting curiosity. People won’t take initiative, won’t take things into their own hands or on their own shoulders.” He goes on to say that a personal relationship with God liberates people from these attitudes.

Kids at a medical clinic enjoying a presentation on good hygiene.

Doctors and translators work together to see over a hundred kids. There are four different areas in this school room for examining the kids.

Waiting to see a doctor.

A kid's eye view of a vision test.

Although the medical system needs a lot of changes and is a work in progress, there are things that can be done now. One thing being done is that our team has partnered with local and foreign doctors and nurses to offer clinics for school children. They are given a basic physical in which they are tested for malaria, among other things. Usually, almost all the children have malaria, many have ears so stopped up that they would have eventually gone deaf if they hadn’t been cleaned out, and some major health problems are found.

At these clinics, the kids are also able to see funny skits which teach them about the value of hygiene and mosquito nets. Although they can be a little scared of the costumes at first because they’ve never seen anything like that, the kids have a lot of fun laughing, participating in the singing, and answering questions about what they just learned.

Entertaining the kids with a song about hygiene. "Say yes, yes, yes to hygiene!" The kids are afraid of the "lion" at first, but soon join in on the fun.

Two "kids" who teach about hygiene. The one with the white patch (representing a fungus some kids can get) doesn't take care of himself and has all kinds of troubles.

Many adults are there as well, hoping to get to see a doctor for free, but this program is just for the kids. The need overflows the ability of a few to provide medical care. Again, so many people wanting medical care for free just emphasizes the poverty of this area in that antibiotics are available for a dollar and yet people feel they can’t afford it. It also highlights attitudes that need to be changed about valuing the health of all people and believing that they are worthy of loving care as much as the “important” people of this world.

What do you think? Have you had an experience helping at medical clinics? Have you ever encountered a cultural viewpoint difference that was challenging? What do you think about the article I mentioned above, especially the illustration about whether or not to climb a mountain?